The CinemaScope Story

To really talk about CinemaScope and its impact on cinema we need to understand a little of what cinema was like pre 1950s. Since its early beginnings the shape of the screen (its aspect ratio) was almost square at around 4 x 3, (4 units wide and 3 units high) and it stayed that way for more than seventy years

Although several early tests had been conducted on wider formats, ‘The Big Trail’ released in 1930 was possibly the most notable. Shot in black and white on 65mm film it was John Wayne’s first lead role, but at the time there was no real impetus for wider formats, so the 4 x 3 box shaped image remained.

There was however something around the corner that would provide that impetus. In the late forties early fifties television began to take hold and studios and cinemas began to see their audience numbers decline. People got used to the idea of being entertained at home from this new box in the corner. Television - it was at first a novelty, but very quickly became a threat to cinema. Interestingly television ultimately copied the same 4 x 3 aspect ratio, a picture shape that people were accustomed to in cinemas.

Television screens at the time were tiny, some less than twelve inches (30cm) across and of course in the beginning black and white. But the small picture in a big box in the corner caused an unrelenting decline in cinema audiences.

Studios looked to what they could offer that television couldn’t. The answer was colour, size and spectacle. So they went big - very big.

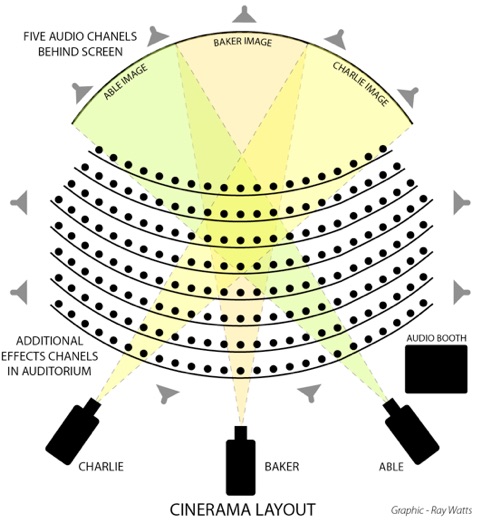

Fred Waller, Lowell Thomas and Mike Todd along with Merian Cooper got together and used a system that Waller had created much earlier but never fully developed, they called it Cinerama. It used a system of three interlocked projectors beaming onto a wide deeply curved screen. This produced an extremely wide 146 degree field of view, close to what we see with our eyes. Not only was it wide but taller too, instead of the standard four perf pulldown each camera frame was six perforations high. This meant an image of unparalleled definition because of the enormous combined frame size. The film was also shot and projected at 26 frames per second instead of the standard 24 and was accompanied by seven track magnetic audio running on a separate 35mm filmstrip. It was the ‘big gun’ that would drag people back to the cinema.

Cinerama was first commercially demonstrated on Broadway on September 30, 1952. The film was called ‘This Is Cinerama’. It was created to demonstrate the potential of Cinerama and of course contained the now famous roller coaster ride that at the time felt so real it induced motion sickness to some people in the audience.

There must be admiration for Waller, Mike Todd and the developers of Cinerama to have had the vision and daring to move cinema technology forward so much in one giant leap. To jump from a flickering 4 x 3 mostly black and white picture to something so massively impressive is astonishing. I was lucky enough to see Cinerama at the Casino Cinerama Theatre in London in the fifties. It was truly an exceptional experience.

But the system had flaws, and there were many. The triple cameras were heavy, bulky and noisy. The three lenses produce odd optical effects when used in close ups, actors had to avoid the ‘seam’ area where the images would join up. Directors felt restricted because close up shots were out of the question and the camera viewfinder could not be used without removing the film reels. Also the cost of equipping theatres with the new system was staggering and almost always it was easier to install in a purpose built building. Even the screen had problems. Because of the deep curvature, light from one side of the screen would wash out the image on the other side. The answer to that was to make the screen from a thousand or more three quarter inch (20mm) wide strips hanging down and each facing square to the audience like a vertical blind. This in itself caused other problems as very loud sounds from speakers behind the screen or air conditioning draught could make the vertical strips move around. The problems were numerous, and even though they tried various tricks, it was impossible to hide those troublesome joins.

Although impressive, Cinerama was never going to be ‘the new way of cinema’ and probably that was realised from the beginning. It was not ever going to be ‘mainstream’ so it was not going to bring back audiences lured away by television. It was not a mass cinema system but merely an impressive oddity.

Cinerama did survive however and there were theatres in many countries right into the 60s, but only eight movies were ever made in the original three strip format.

One exception was ‘In The Picture’ where an old Cinerama camera was dusted off and refurbished in 2012 to shoot a true Cinerama picture to mark sixty years since Cinerama opened. The system of Cinerama did continue but movies were shot in single camera systems and printed to three strip Cinerama film for projection.

As of 2022 there were only three Cinerama theatres left in the world. Sadly two of those, The Cinerama Dome in LA and Cinerama in Seattle fell victim to Covid and are now ‘Closed indefinitely’. The only one left in the world is The Pictureville Cinema at The National Science and Media Museum in Bradford UK. So if you choose the right weekend you can still see three strip Cinerama projected as it was back in the 50s.

Cinerama was a unique cinema system, big, bold, and spectacular, but in the end just an awkward, expensive novelty.

To combat television the studios needed a system that could produce an impressively wide picture but also allow directors to use standard 35mm film and equipment. A system that would not take away filmmakers freedom to choose what shots or what lenses to use, and also one that would be relatively cheap for exhibitors to install.

20th Century Fox found the answer across the Atlantic in France.

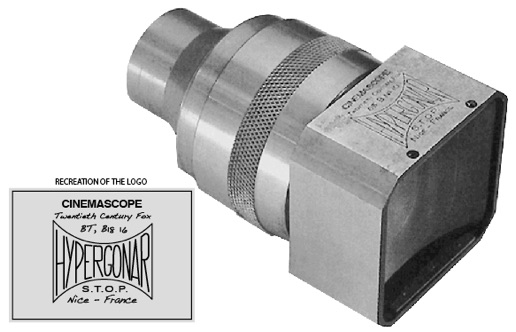

In 1890 Ernst Abbe and the Zeiss Co in Germany developed a lens with cylindrical elements that had the ability to squeeze images in one direction, this is probably the earliest mention of anamorphic lenses.

Henri Chrétien, a french astronomer and inventor, equipped with a great mind and practical ability made further developments in France to make the lens suitable for motion pictures, he named the lens Hypergonar. The lens had the ability to capture a very wide field of view, something that at the time was not possible with spherical lenses. Chrétien could also see a use for the lens in the three strip colour experiments of the time in squeezing the red green and blue images onto one film strip.

He set up a company ‘Societe Tech-nique d'Optique et de Photographie’ (Technical Society of Optics and Photography) to manufacture the Hypergonar lenses. The company produced many of the lenses and they can still be found today. But Henri Chrétien had trouble getting the movie industry interested in his lenses. As early as 1928 Chrétien presented a demonstration to Paramount but they did not proceed to use his lens.

On December 13th 1952 Fox executives were shown a black and white film that had been shot with Chrétien’s anamorphic lens. They were impressed but at the time the lenses were licensed to the J Arthur Rank Organisation, a film studio in the UK. The Rank company had done little with the lens but Fox had to wait for the Rank licence to expire before they could take the lenses back to Hollywood.

On January 20th 1952 three of Chrétien’s anamorphic lenses arrived at the Fox Studios.

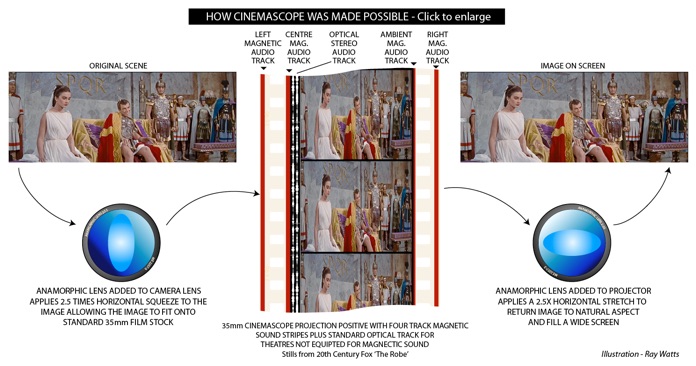

Fox’s laboratory set about implementing a new wide screen system. By adding the lens to the front of a camera an extra wide view could be photographed. The horizontal axis was compressed roughly two and a half times while the vertical aspect remained the same. The squeezed image could be placed on standard 35mm movie film. A similar lens had to be put in front of the projector to de-squeeze the image onto the screen giving a wide view and an aspect ratio of about 2.55:1. Fox were very pleased with the results and set in production two pictures to be shot with the new lenses. But how could they market this new process? They needed a name, something that would suggest something really new and exiting.

Chrétien's name for the lens, Hypergonar, didn’t exactly roll off the tongue, they needed a name with more appeal. Television station KCOP Channel 13 in Los Angeles had registered a process for recording TV shows onto film. They called their process Cinemascope. Fox liked the name so they paid the station $50,000 for the trademark and 20th Century Fox CinemaScope was born.

On the 16th September 1953 the first CinemaScope picture was presented at The Roxy Theatre in New York. ‘The Robe’ with Richard Burton, Victor Mature and Jean Simmons was a biblical epic with a cast of thousands. Presented on a screen that was not only two and a half times wider but also taller than anything that had been seen before. The sound was from four magnetic tracks one each side of the sprocket holes that fed speakers left, centre, right behind the screen and also an ‘ambient’ effects track around the auditorium. The film also carried a traditional optical track for theatres not equipped for magnetic sound. The overall effect was incredible and it received an ecstatic reception from the star-studded audience.

Fox quickly announced all future pictures would be now shot in CinemaScope. Almost as quickly other studios began to develop their own systems but ultimately were able to licence CinemaScope from Fox - at a substantial fee of course.

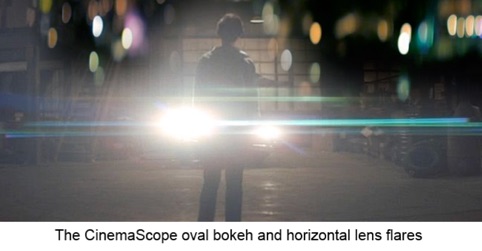

Many pictures were made in CinemaScope during the ’50s and 60’s and the public did start to return to the cinema. But something came from it that was not expected. It was soon noticed that CinemaScope movies had a different look, apart from their wide aspect ratio they conveyed something beyond size. Bokeh, that out of focus area of a shot looked different in Scope, instead of the normal round bubble like patches of light the bokeh from a CinemaScope image had oval balloon shapes and lens flares from car headlights took on an entirely different look with wide horizontal flashes of blue sometimes green dramatically flashing across the screen. The CinemaScope process applied a nuance to the image that added dramatic weight to a scene. It had earlier been seen as a flaw but soon became a sought after effect.

But the anamorphic CinemaScope lens did have a softening effect on the image no matter how slight and there were inconsistencies in the stretch between the sides and the centre of the image. When actors moved to the centre of the screen they appeared slightly wider, an anomaly referred to as ‘The Mumps’. Also standard Academy ratio had black bars between each frame to hide the splice marks that were inevitable when the negative was edited and the many pieces of film joined together. Fox decided to increase the height of the frame so their squeezed image used this space between frames as well. The result of this decision can be seen in early CinemaScope pictures where a white line flashes across the top of the screen with every cut. With better anamorphic lenses produced by Bausch & Lomb most of these problems were resolved and fortunately the unique bokeh and dramatic lens flares remained.

Digital cameras today can shoot wide without using an anamorphic lens but some filmmakers continue to put a ‘Scope’ lens on the front end to get the nostalgic CinemaScope look. “If it’s not wide and in ‘Scope’ then it aint a real movie!”

The effect of the CinemaScope widescreen format echoes to this day. When our high definition digital television standard was being formulated it was decided that 16 x 9 was the best aspect ratio to give both 4 x 3 movies and 2.35:1 widescreen movies equal screen space. So black bars top and bottom when showing a wide screen movie roughly equate to the same area as black bars each side when showing a 4 x 3 movie. Your brand new 100 inch 4K television owes its aspect ratio to a CinemaScope shape forged back in the ’50s.

A FEW NOTES:

1. The intention of this article is to explain in a simple, clear way the advent of CinemaScope. There were several other formats being developed and used in the fifties and sixties not covered here.

2. A wide 2.35:1 aspect ratio on its own is not necessarily CinemaScope, although today many people refer to every wide format as such. CinemaScope was a proprietary system developed by 20th Century Fox using an anamorphic lens to compress a wide field of view onto a standard 35mm film frame. As mentioned above it has its own optical characteristics that have become sought after today. Non anamorphic wide processes do not have CinemaScopes optical characteristics and should not be referred to as CinemaScope.

3. Henri Chrétien’s company in France continued making anamorphic lenses into the sixties. Oddly they got the rights from Fox to use the word CinemaScope along with the original name of Hypergonar on their lenses. Many French films were made using these lenses.

-

4.Kinopanorama was a three strip system virtually identical to Cinerama conceived in the Soviet Union around 1956/7. It was exhibited in a number of countries. Oddly Fifth Continent Movie Classics in Australia secured Kinopanorama camera No.6. The camera is available for hire to anyone brave enough to consider a Kinopanorama project! They also registered a unique Kinopanorama logo to differentiate movies made with the camera in Australia and the previous soviet films.

CREDITS

‘This Is Cinerama’ - Fox YouTube

Wikipedia

‘In The Picture’ - documentary YouTube

American WideScreen Museum

Article written as non profit and for information only.

Ray Watts (2022)